Bethany Herron

Instructional Designer

Read more from Bethany

Scott Centorino

Senior Fellow, FGA

Read more from Scott

This article was originally published in The Joplin Globe on November 14, 2022.

I (Bethany Herron) became familiar with the brokenness of the child care system as an instructional designer for True Charity Initiative. Through my work, I have heard many stories of hardworking parents who have faced the prospect of having their kids placed into foster care due to an inability to find safe and affordable child care options while they are away at work.

In a recent conversation, Jennifer Johnson, a former lawyer turned child care cooperative director, told me, “Many of the women (she) represented were good mothers. They loved and desired to parent their children. However, they just couldn’t figure out how to work and pay for child care.” Jennifer’s story represents similar conversations that I have had with pregnancy care center directors, child care centers and nonprofit leaders.

Recently, I (Scott Centorino) have seen that same brokenness from a new and life-changing angle — parenthood. I used to see child care access and affordability as distant reasons to write op-eds on broken public policies. But as a father, sitting on a waiting list to get my newborn into the only child care center in our rural county that serves infants, the child care crisis has become personal.

We, along with countless parents across the nation, agree it’s time to introduce solutions that increase access to safe, affordable and flexible child care that help ease the burden for parents who just want to provide for their families.

Over the past three years, more parental rights and less unilateral bureaucratic control have become popular solutions for access to quality education in public schools. It’s time we take the same approach to child care.

Throughout the pandemic, communities banded together to lift up their own. Child care cooperatives, nanny shares and outdoor learning pods — also known as microschools — popped up across the nation. This was made possible through temporary suspensions of child care regulations in areas ranging from staff-to-child ratios and group size limits to physical space restrictions and educational requirements for workers. These changes were made to drive down the cost and drive up the supply of child care.

Predictably, the free market worked. Communities used their creativity and ingenuity to develop solutions to a crisis that allowed qualified individuals to care for more children while keeping kids safe.

Continuation of these model community solutions, unimpeded by bureaucratic interference, could help young single mothers form child care co-ops so they can attend school or work. Driven couples striving to transition from government assistance could share the child care burden between families. Yet, in many states, this kind of community-driven effort is illegal under restrictive child care licensure laws.

Even before the pandemic, the average family with children under 5 spent 13% of their income on child care, 5% more than the upper limit of what is considered “affordable.” This number is only going to climb as we face record inflation.

The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis has released a new study showing that more flexibility in staff-to-child ratios could help keep costs down for families. This mirrors a report by the Mercatus Center published seven years ago.

If, during the pandemic, policymakers understood that simply letting parents choose from a greater number of less restricted child care providers would help families, why shouldn’t the government do the same now? Reducing staff-to-child ratios will expand access to affordable care that allows parents to work and better avoid the pitfalls of government dependency.

With this new inflation crisis and worker shortages, the last thing we need is higher child care costs and more parents leaving the workforce.

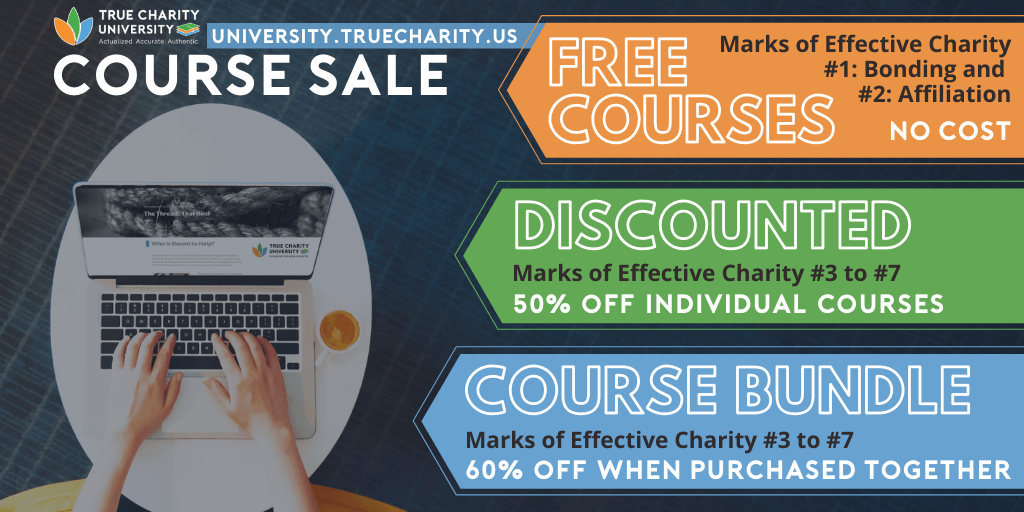

Want to learn about solutions for your community to help ease the burden of child care for those in poverty? The Childcare Solutions Model Action Plan (MAP) provides ideas and practical steps to do just that. (Learn more about MAPs.)

MAPs are just the tip of the iceberg for the practical resources available through the True Charity Network. Check out all of the ways the network can help you learn, connect, and influence here.

Already a member? Get access to all of your benefits through the member portal, including the Childcare Solutions MAP.

FROM THE TRUE CHARITY TEAM: We appreciate the perspective of our knowledgeable guest contributors. However, their opinions are their own, and do not necessarily represent positions of True Charity in all respects.